But a transaction of principal interest

here involves the sale by the grantees and their heirs of 1100 acres in the

very heart of Deep Creek – the Bryson Place – and an interconnected 100-acre

purchase a few miles downstream.

Will Thomas and T.D.

Bryson strike an agreement

On September 21, 1868, Will Thomas signed an agreement

which read:

I

agree to let Col. Thadeus (sic) D. Bryson have the unimproved Martin tract of land on Deep Creek,

including one hundred acres to be run in a square or oblong square to include

the Martin improvement for the sum which the land and improvements may be

valued to be worth at green back prices by John Millsaps, Wm Cathey, & Lt.

Wm Morris or a majority of them.

And

I agree to make a title for said land to the said Bryson or his Assignee upon

credit being given on our own contract.

Green back rates

Sept.

21 1868

Wm.

H. Thomas

We

the undersigned referees have examined the Land and value the same at one

hundred and fifty dollars in Green Back.

Oct.

24th 1868 Wm.

L. Morris

John

A. Millsaps

Wm.

H. Cathey

The wording of the agreement is confused – Thomas

agreed to let Thaddeus Dillard (T.D.) Bryson acquire an unimproved

Martin tract which included the 100 acres of the Martin Improvement – an

utter non sequitur. As we’ll see, the apparent

intent was to express his willingness to sell 100 acres of land which had been

improved by the Martins, with the improved section accompanied by an

unspecified area of unimproved land.

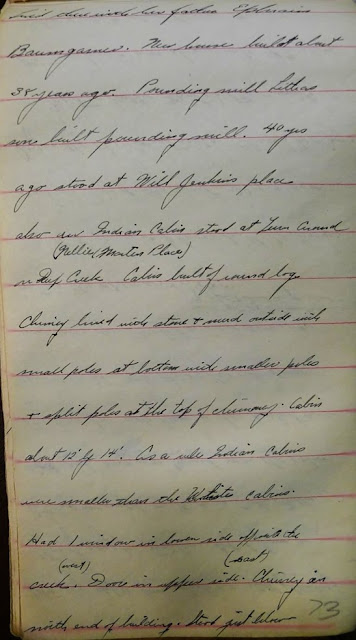

The Martin Improvement would later be known as the

Bryson Place. A photo of the Bryson

Place cabin taken almost 70 years later (1937) by Charles Grossman is shown in

Figure DC2. Clearly, instead of a single

cabin, it is actually two cabins built at different times, with a small gap in

between the outer walls, but connected by an internal passageway. While the portion on the left has stovepipes

sticking out the roof, it originally had only a chimney at the far left. Could one of these two sections have been the

cabin of the Martin Improvement?

Another, more likely possibility, appears in a photo

from the Horace Kephart Special Collection at Western Carolina’s Hunter Library

shown in Figure DC3. The smaller

structure in the foreground of this undated photo (likely around 1910) does not

appear in later photographs of the Bryson Place. The small, south-facing window is similar to

that of the smaller Bumgarner cabin shown in Figure WM1 in Wendy’s accompanying piece.

As noted by Charles Grossman, that smaller cabin was Cherokee-built, and

the same may very well be true here. The

fruit trees, both in the foreground behind the unknown couple and in the left

background, beyond the cabin, appear large enough to be several decades old.

Regardless of which – if either – of the cabins in these photos was erected by the Martins, in 1868, they were clearly living at the place which Thomas agreed to sell, had been living there long enough to have cleared the land, build a cabin, and made the other necessary changes to warrant the title “Martin Improvement.”

It seems entirely possible that the confused wording in

the agreement was a result of Will Thomas’s dementia; he was declared insane

the year before signing the agreement.

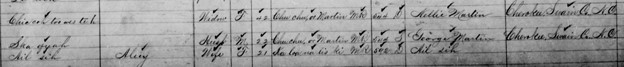

Less than two years later, when the 1870 Jackson County census was

recorded, 64-year old W.H. Thomas was the first person listed in the Qualla

District. His profession was given as

State Senator, Merchant & Farmer. In

the column reserved for identifying ailments, he was listed as “Insane.” Thomas had formerly served as State Senator,

but was not serving in 1870, and in fact had not served in that capacity since

1862.

All of the individuals named in the agreement would

have been well acquainted The three

referees – Billy Morris, John Millsaps and William Hillman “Hill” Cathey – were

all residents of the Deep Creek area.

Millsaps was a physician; Morris and Cathey had served in the Civil War

and were brothers-in-law (Cathey’s wife was Nancy Morris, sister of Billy). Millsaps and Morris in particular owned

considerable lands on Deep Creek.

Cathey’s place on Indian Creek was relatively small in proportion, but

was still in excess of 150 acres. Bryson

and Thomas would have been well acquainted, as both had represented Jackson

County in the state legislature (Bryson in the House, Thomas in the

Senate). Hill Cathey served in Thomas’s

Legion during the Civil War.

The agreement which Thomas signed wasn’t proven until

fifteen years later, when Probate Judge W.A. Gibson approved it on Nov. 3, 1883

and it was registered the same day by Nathan Byers Thompson, Register of

Deeds. This delay may have been a factor

in the next subject – duplicate deeds.

|

Figure

DC4. Billy Morris, home place. This site is located just above the parking lot at the gate to the Deep Creek trail. Morris

photo courtesy of Jim Estes. Home photo: Open Parks Network |

Deeds in duplicate

On May 23, 1878, T.D. Bryson purchased 1,100 acres of

land on Deep Creek in two separate tracts – a 1,000 acre tract and a 100 acre

tract. The boundaries were not

defined. The deed read:

The

undersigned do this day sell to TD Bryson one thousand acres of land on Deep

Creek in Swain County and adjoining lands lately purchased from Wm H Thomas and

now occupied by Samuel Elliott at 33-1/3 cents per acre

and also one hundred acres adjoining Geo. Shuler on Deep Creek where Joe

Feather lives at one dollar and fifty cents per acre and we authorize E Everett

to make deeds in pursuance to a power of attorney now effected reserving ¾ of

the minerals in the lands this 23rd of May 1878. The said parties acknowledge the payment therefore

by a credit of one hundred and twenty dollars on RV Welch’s note and three

hundred and sixty three on Samuel L. Love’s note to be surveyed at the costs of

the undersigned this 23rd May 1878.

Atest

(sic) RV

Welch

E

Everett RGA

Love

W.L.

Hilliard

RM

Henry Saml

L Love

The wording of the deed is – somewhat like the

agreement language – jumbled in that it says the one thousand acres adjoins

lands lately purchased, yet the adjoining one hundred acres is specified

after the thousand acres in the deed.

Regardless, the 100 acre tract is clearly the same one referred to as

the Martin improvement in the 1868 agreement; the price is that indicated by

referees Billy Morris, Hill Cathey, and John Millsaps. It is noteworthy that in the ten years since

the agreement signed by Thomas, Samuel Elliott had begun to occupy the

unimproved section and Joe Feather (a Cherokee man) was then living on what was

previously described as the Martin improvement.

No record has been found of George Shuler owning land within miles of

this area. Joe Feather and his family are mentioned in the 1880 census, but his

and another Indian family appear to be located in the Galbraith to Cooper Creek

section.

A year and a half later, on November 4, 1879, the deed

was proven in the probate court of Samuel B. Gibson, who ordered it to be

registered. No boundaries were given in

the deed; the entire deed is listed above.

Notably, the deed was proven in court one day shy of four years before

the original agreement, as noted above.

It was not unusual for deeds to be registered more

than once in the early years of Swain County, in part due to nuances in the

legal process. The land which would

become known as the Bryson Place was one such example.

On May 25, 1879, a year and two days after deeding

both the 1,000 and 100 acre tracts to T.D. Bryson, the Loves, Welch, and

Hilliard, along with their agent Epp Everett, created a deed for the 1,000 acre

tract to Mary C. Bryson (wife of T.D. Bryson), but this time with boundaries

specified:

Beginning on a

pine in the line of a hundred acre tract bought by T.D. Bryson of W.H. Thomas,

runs North 62 East 229 poles to a stake, thence North 28 West 439 poles to a

stake; thence South 62 West 389 poles to a stake; then South 28 East 389 poles

to a stake in the line of said hundred acre tract; thence with its line North

62 East 160 poles to a chestnut, its beginning corner; thence with said line

South 28 East 50 poles to the beginning.

The deed noted that this formerly unimproved tract was

now “known as the place where Elliott now lives.” Sam Hunnicutt, in 20 Years Hunting and Fishing in the

Great Smoky Mountains, referenced the Elliott place as

both a Camp and an Improvement. The area

today is boggy and rhododendron-infested.

Exactly where the camp or improvement was located is unknown.

Then on November 15, 1883, “W.L. Hilliard, of Buncombe

County, North Carolina, Guardian of Wm. H. Thomas, a lunatic”, executed a deed

to Mrs. M.C. Bryson, assignee of T.D. Bryson of Swain County for the one

hundred acre Martin improvement, and explicitly noted that the bond associated

with the agreement had been registered in book D (4) pages 103-104. With Thomas having serious financial issues,

the $150 payment was made by crediting Thomas’s indebtedness to Bryson, which

was over $900.

It appears that, in part, this second edition of the

deed was established to acknowledge that the original agreement signed by Will

Thomas had not been registered until Nov 3, twelve days before this deed to

Mary. But in addition, while the earlier

deed to TD Bryson provided no boundary calls, the deed to Mary Bryson did:

Beginning on a

chestnut and runs South 28 East ninety poles to a stake, passing a pine, the

beginning corner of a one thousand acre tract bought by T.D. Bryson from the

Executors of Jas R. Love & R.V. Welch at fifty poles (then) South 62 West

one hundred and eighty poles to a stake, then North 28 West ninety poles to a stake,

thence North 62 East one hundred and eighty poles to the beginning, passing a

corner of the said thousand acre tract at twenty poles and containing one

hundred acres.

The deed notes that it includes “what was known

as the Martin improvement” – connecting it to the original agreement signed by

Thomas in 1868.

Seeing Nellie Home

On the same day that the original deed from the

extended Love family (Hilliard, Welch and their Love brothers-in-law) to T.D.

Bryson was registered – November 4, 1879 – agent Epp Everett, acting on behalf

of W.L. Hilliard, S.L. Love, R.V. Welch and R.G.A. Love, executed and had

registered another deed which read:

Know

all men by these presents that we Wm L Hilliard, SL Love and RGA Love as

executors of James R. Love and RGA Love and RV Welch for themselves by their

agent E Everett have this day bargained and sold unto Nelly Chis-esli (Indian)

one hundred acres of land in the County of Swain and State of North Carolina on

boath (sic) sides of Deep Creek above and adjoining tract of land known as the Corntassel

place for the sum of one hundred and fifty dollars paid to said parties of

the first part by TD Bryson the payment whereof is hereby acknowledged.

This tract embraced the land which included the

section which has long been known as the Turnaround. A photograph of the Turnaround appears in

Wendy’s article Figure WM7.

|

| Figure DC5. Portrait of T.D. Bryson in Swain County’s Administration

Building, courtesy of the Bryson family. |

What led T.D. Bryson to purchase the land for Nellie

and the rest of her Martin family?

Both the Martin improvement and the land at the Turnaround

involved a nominal 100 acres and the price for each was the same: $150. That suggests that there was already some

sort of improvement in the area of the Turnaround since there is nothing

regarding other characteristics of the land which would make it more valuable

(excepting its closer proximity to other families). In Wendy’s piece on the Martins, she offers a well-thought out conjecture, namely that

Bryson was looking out for the welfare of the Martins, a family which was under

significant stresses at the time. It is

also reasonable to assume that Will Thomas’s concern for them was a key element

of the arrangement.

The deed defined the boundaries of the tract and its

relation to the Corn Tassel Place – which adjoined it. In Figure DC6, the combined Bryson tracts, as

laid out by the N.C. Park Commission, the tract purchased by T.D. Bryson for

Nellie, and the Corn Tassel Place tract are marked in relation to the overall

Deep Creek drainage. Also indicated are

the Bumgarner Place and the Deep Creek trailhead, located at the mouth of Juney

Whank Branch. The upper end of today’s

parking lot sits immediately in front of where the Billy Morris home place

stood.

|

| Figure DC6. Map of locations within the Deep Creek drainage (by author). CLICK HERE for a detailed topo. |

The map snippet in Figure DC7 shows the Bryson Place

tract based on the deed from the Bryson family to the N.C. Park

Commission. The Bryson Place cabin stood

at the extreme lower end of the tract (marked with the black dot). The Martins Gap Trail comes across from

Indian Creek, passes through from Martins Gap on its way down to the Bryson

Place; both can be seen at the lower right portion of the map. The gap and trail were obviously named for

Nellie and her family. Just north of the

cabin, Elliott Cove Branch empties into Deep Creek from the east, named for

Samuel Elliott who occupied (but did not own) the land when the Brysons

purchased it. Above it, Pole Road Creek,

named for a pole road used to extract lumber from its boundary, enters from the

west. Then just above the geographic center

of the tract, Left Fork joins Deep Creek’s main prong.

|

| Figure DC7. Map of the Bryson Place tract (by author) |

The map of the Bryson tract as mapped by the NC Park

Commission varied slightly from the original dual tract deed. That most likely had to do with survey

methods of the 1870s vs those used by William Neville Sloan, a native of

Franklin and great-grandson of Jesse Richardson Siler, namesake of Silers

Bald. Sloan trained in engineering at

North Carolina State College in Raleigh and came back to his mountain home land

to practice both surveying and engineering.

The survey

of this tract, and for that matter, every tract

purchased by the NC State Park Commission lists Sloan as the surveyor. Sloan was assisted by chain bearers and brush

clearers the likes of Mark Cathey (a son of Hill Cathey) and Sam

Hunnicutt. Hiram Wilburn, who also

worked for the Park Commission, noted that Mark Cathey, who was in his upper

50s at the time, could clear brush twice as fast as men half his age.

The children of T.D. and Mary Bryson – Judge T.D.

Bryson, Dr. Daniel Rice Bryson and their missionary sister, Mary Bryson Tipton

– allowed both the Bryson cabin and the boundary to be used as a community

commons. The community which benefitted

– including the family of the author – failed to fully acknowledge and

appreciate the Bryson family spirit of sharing not only this but other Bryson

lands in Bryson City, the town named for their father. Cathey, Hunnicutt, and dozens of others (including

the author’s father) spent countless nights at the old cabin. Days were spent wandering the roughs and

wading streams of Pole Road, Left Fork, Elliott Cove Branch, Nettle Creek and

the entire upper reaches of Deep Creek, all because the Bryson family shared

with the community, including the folks of the town named for T.D. Bryson,

Sr.

In stark contrast, such was not the case with large

tracts of land acquired by individuals who did not make their home here. Phillip Rust, a wealthy Boston native who

married Eleanor Dupont, great-granddaughter of the founder of the Dupont

Corporation, hired wardens to patrol his 4,365 acre estate on Noland Creek. The Stikeleather-Smathers group, largely

composed of individuals from Asheville, did the same for their 7600 acre Hazel

Creek estate, composed of lands acquired after Ritter Lumber left Hazel Creek.

Both estates were established after the original Park formation. The lands were posted and the local hoi

polloi were run off by the wardens.

How bittersweet the survey work must’ve been for Cathey,

Hunnicutt and others who recalled days of hunting, fishing, and backwoods companions

who included preachers, teachers, politicians, a convicted murderer,

northeastern blue bloods of the first rank, and fellow branch water folk. In his classic 20 Years Hunting and Fishing in the

Great Smoky Mountains, Sam Hunnicutt names men whose lives

in so-called civilization matched those categories, but he never mentioned

anything about them personally; his was an egalitarian outlook. In Sam’s eyes, those wandering the wilds of

the Great Smoky Mountains were fellow creatures in an especially sweet part of

God’s creation – a place where neither social rank nor fortune was a

consideration.

The Hunnicutts had their

own special connection to the Turnaround area.

An enlargement of the area where the 100 acre tract purchased by T.D.

Bryson for Nellie and her Martin family is shown along with the Corn Tassel

Place tract in Figure DC8. The Jenkins

Place home stood along Deep Creek immediately to the east of the uppermost

bridge where the Deep Creek loop trail connects. Other area features are highlighted,

including three separate home places on both sides of Deep Creek which were, at

one time or another, occupied by various members of the Hunnicutt family.

|

| Figure DC8. Martin & Corn Tassel Tracts in relation to the homes of Billy Morris and Hill Cathey (Map by author). |

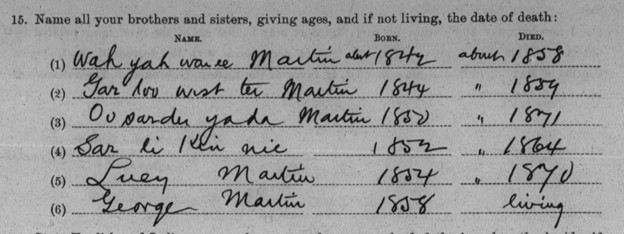

Nellie’s family

leaves Deep Creek

On August 31, 1885, the Martin Turnaround tract was

sold. The deed reads:

This Indenture

made and entered into this the 31st day of August A.D. 1885 by and

between Suate Martin and his wife Da-ga-nu Martin and Geo. Martin heirs of

Nellie Chis-e-li deceased of the County of Swain and State of North Carolina,

parties of the first part and Wm P. Shuler of the Same County and State part of

the second part. Witnesseth: That the

said party of the first part for and in consideration of the sum of two hundred

dollars to them in hand paid…..

Nellie

had been listed in the 1884 Hester Roll, so her death occurred between 1884 and the end of August

of 1885. In that 1880 census, her age

was given as 35, suggesting a birth year of around 1845 – thus the range of

life listed for Nellie on her cenotaph marker in the Turnaround as circa

1845-1885.

The Martin property was sold to William Payton “Pate”

Shuler in 1885. In 1895, Shuler and his

wife, Narcissus, sold the Martin tract as well as the Corn Tassel tract (which

had been acquired separately) to George Jenkins. Around the first decade of the 1900s, Jenkins

erected a two-story home on the east side of Deep Creek (see Figure DC9) and

farmed the land on both sides of the creek, including the Jenkins Fields which

extended from just below the last bridge on Deep Creek almost half a mile down

the west side of Deep Creek.

|

| Figure DC9. Jenkins Place home in 1937, several years after it was abandoned. Source: Open Parks Network |

In 1908, Jenkins and his wife, Cora, sold the entire

Martin tract to William Spurgeon Hunnicutt for $150 – the same price that T.D.

Bryson had paid the Love heirs almost three decades before. Although there had been improvements made by

the Martins, the improvement value had been lost to nature and time. In 1912, Spurgeon Hunnicutt and his wife, Lottie, set

off the eastern part of the property and sold it to Spurgeon’s oldest brother,

Waitsel Avery Hunnicutt. The deed

language proved to be a significant element in our assessment of the actual

location of Nellie’s grave and home. It

read:

"Beginning on a bunch of white

walnuts in the old Corn Tassel line on the east side of Deep Creek at the lore (sic)

end of the old field & runs up said creek 38 poles to a chestnut on bank of

Deep Creek then NE with the meanders of the Indian Grave Ridge to the

old line then S71E 57 poles to a stake and pointers thence S 40 poles to a

stake the line of said Corn Tassel Place then with this line W 79 poles to the

beginning. Containing 35 acres more or less being a part of the tract of

land bought from Georg. W. Jenkins of one hundred achears (sic).”

The section of the

original Martin tract which Waitsel purchased is marked in yellow in Figure

DC10. The reference to Indian Grave

Ridge is the first that has been found.

It continued to be used up until the time the land was taken by the N.C.

Park Commission. A closer relative

perspective which includes the elements noted below as well as the Turnaround

road and ford locations is provided in Figure DC13.

|

| Figure DC10. Original Martin Tract purchased by Spurgeon Hunnicutt, with the eastern section sold to his brother Waitsel highlighted and the Indian Grave Ridge which was part of the boundary noted. Map by author. |

Family patriarch, Marion Hunnicutt, died around 1904

and his son, Christopher Columbus Hunnicutt, died in 1923, per the Hunnicutt

family. According to family tradition,

father and son were buried on Indian Grave Ridge, just above the home which had

been built there. The home was logically

sited immediately adjacent to a spring. On the other hand, the concept of siting a home in the

middle of the almost level bottomland of the Turnaround, and also more than 100

yards away from a spring, would be at complete odds with virtually universal

practice of Smoky mountain settlers, whether Cherokee or White. As Wendy and I have considered the overall

layout of the Turnaround area, we have concluded that by far the most logical

location for Nellie’s home was exactly the same location as that chosen by the

Hunnicutts along the lower end of Indian Grave Ridge. The spring was right next

to the house and siting the home there also didn’t occupy the most arable land.

Conservation of bottomland was such a

priority that the original road up Deep Creek was cut into the side of the

hills in order to keep all of the best land free for raising of crops. The spring for the Waitsel Hunnicutt home –

which we also believe to Nellie’s home – is shown in Figure DC11. Wendy Meyers is standing in the old road,

which wound around the slope on the east side of the creek. The old wagon road begins on the east side of

the former ford at the Jenkins Place and connects to today’s Deep Creek Trail

at a rock wall which was built by the Hunnicutts, according to family

tradition.

|

| Figure DC11. Spring next to the Waitsel Hunnicutt home; Wendy Meyers is standing above the spring next to the old road which wound around the side of the ridge instead of along the precious bottomland. |

Finally, the fact that Will Jenkins reported that her

burial was adjacent to the house also fits well with naming the ridge “Indian

Grave Ridge” – since both the home and graves were at the nose of that ridge.Waitsel sold the tract he had purchased from Spurgeon

to Ed and Mollie Shuler in 1925. They

retained ownership until the land was taken by the NC Park Commission. Another tract of land which had formerly been

owned by the Hunnicutts included the Turnaround proper as well as land on the

west side of Deep Creek. When taken by

the N.C. Park Commission, it was owned by Tom and May Edwards. The Park Commission report indicated it was “a

six-roomed ceiled and weather-boarded house in good (repair) located on three

acres of level land, beside the creek.”.

No one was living in the home, which was “being held for recreation

purposes.”

A

Serendipitous Homecoming

Around 2002, Jim Estes was walking up the Deep Creek

trail to fish above the Bumgarner Bend when he encountered a fellow in his

early 80s at the Turnaround. The older

fellow had been fishing himself, but was seated on the log of a fallen tree

waiting on a nephew to finish fishing.

It turned out that the fellow was James Hunnicutt, the youngest son of

Sam and Leah Hunnicutt. James was born

at the mouth of Hammer Branch in 1921, but pointed Jim to where the family had

last lived – at a home site on the other side of the old ford at the Turnaround. It was the six-room house mentioned in the

Park Commission report. That home is one

which was incorrectly marked on the 1931 map of the

eastern section of the Park.

That map showed the home on the eastern side of the creek, but both the

N.C. Park Commission records and extant physical evidence (see Figure DC12) place

it across the creek, near the Turnaround ford, as shown in Figure DC13. I likely would’ve never located that spot had

it not been for Jim Estes passing along the personal memories of James

Hunnicutt.

|

| Figure DC12: Author with yellowbells/forsythia, chimney remains at the Hunnicutt home place across Deep Creek from the Turnaround. |

|

| Figure DC13: Layout of the Turnaround area and features which have been discussed. Map by author. |

James noted that his extended family also

had another home place just southeast of the Turnaround – where his grandfather

Marion and Uncle Christopher Columbus Hunnicutt are buried. See Wendy’s Figure WM8. Jim Estes was himself raised on Deep Creek. His folks, including g-g grandparents Billy

and Sarah Louisa Morris and g-grandparents Goldman and Harriett Estes, were

living on Deep Creek when the Martin family moved to the Turnaround. His family knew the Hunnicutts well.

Those two sons of the Smokies had a homecoming-like

sharing of memories of their common family lore. In the Figure DC14 photo, Sam Hunnicutt is

standing at the left, with frying pan in hand.

The man and woman to the right of Sam may be a Reeves couple, according

to Jim Estes. Jim’s grandfather, Ellis

Estes is on the horse. To the right of

the horse are Tom Clark, Cora McCracken Estes (expecting Jim’s father, Jack,

born in July, 1917), and Laura Estes Clark.

Rena Cagle, the daughter of Lee and Annie Clark Cagle who Wendy wrote about previously is in the white hat behind unknown boys in

front and Bonnie Rogers is to their right.

|

| Figure DC14: Group of Deep Creek folks on a fishing outing. Photo courtesy of Jim Estes. |

Deep Creek calls its own

Deep Creek called to James Hunnicutt and Jim Estes,

for it is a place that calls its children home – to cast flies in holes named

by their forebears decades before, visit old home places, drink from the same

rocked-in springs that quenched the thirst of their ancestors, to recall their oft-told

tales and to simply remember.

The Places of Beard, Blanton, Bryson, Bumgarner,

Cagle, Casada, Cathey, Clark, Cline, Corn Tassel, Durham, Estes, Hunnicutt, Hyatt,

Jenkins, June Whank, Laney, Lollis, Martin, Massie, McCracken, Monteith,

Morris, Morrow, Parris, Queen, Randall, Shuler, Shytles, Styles, Swaim, Teague,

Thomas, Waycaster, Wiggins, and others are integral to the history of the Deep

Creek drainage.

Today, fallen chimneys, rock walls or foundation

stones, boxwoods, daffodils, yellowbells, japonica, mock orange and the like are

visual markers for the former home places.

They are all now Pondering Places, where in solitude or with a small

company, lives once eked out with the combination of a Protestant work ethic

and then common (now rare) know how are remembered. We owe it to them and ourselves to also

recall acts of sympathetic generosity like that of the Brysons for the Martin

family and the community at large.

Precious memories, may they linger….

_________________________________________

Sources:

Jim Estes, Wendy Meyers,

Annette Hartigan, Mike Aday, Ed and Dan Bryson, Jason Brady

NCPedia

article, Thomas, William Holland (gives date of him being

declared insane as March 1867)

NC Park Commission

Records, NC State Archives

Swain County Register of Deeds

Ancestry.com

Note: questions for the author of this piece, Don Casada, may be directed to him at doncasada@hotmail.com.

.jpg)

.JPG)

.png)

%20(ancestry.com).jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)